Aloitan siitä, mitä tiedetään varmuudella. Hypnerotomachia Poliphilin painoi renessanssin merkittävin kirjanpainaja Aldus Manutius Venetsiassa vuonna 1499. Kirja on renessanssiajan kirjapainotaidon ja typografian merkkiteos. Nykyisin vuoden 1499 ensipainos kirjasta maksaa (yksilöstä riippuen) noin 150 000 – 500 000€.

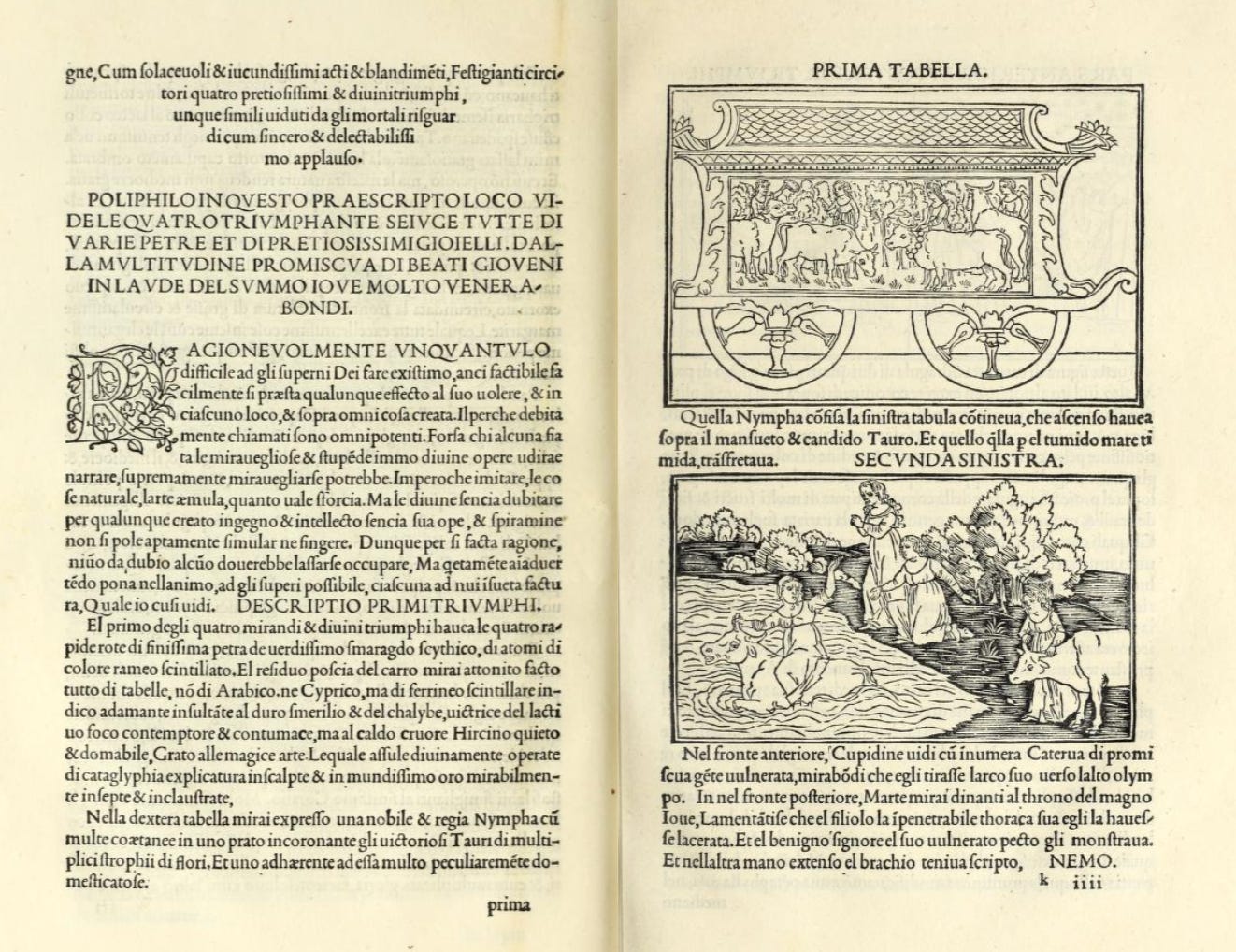

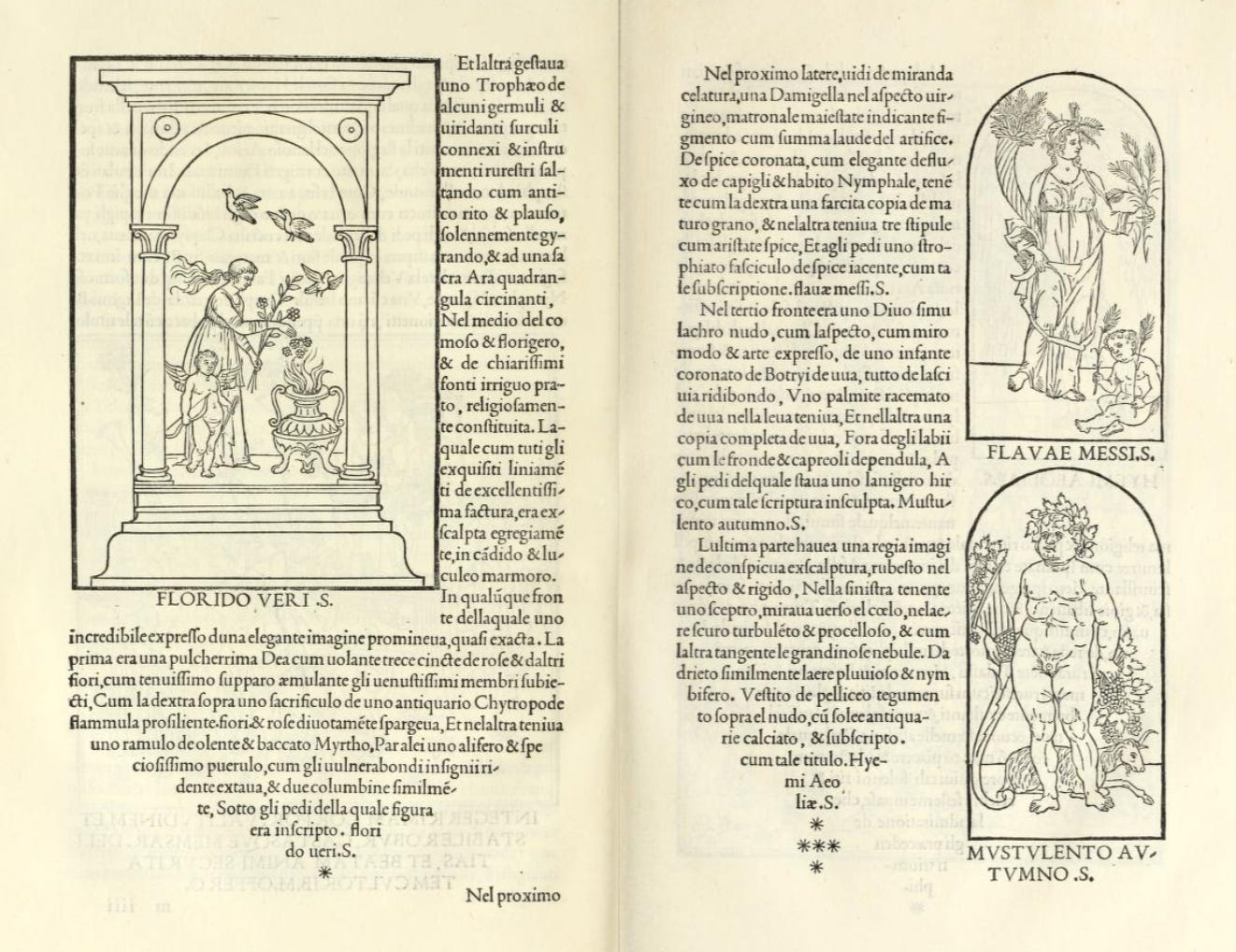

Se, mitä ei tiedetä varmuudella, on kuka Hypnerotomachia Poliphilin kirjoitti tai kuvitti. Kirja julkaistiin anonyymisti, ilman minkäänlaista mainintaan sen kirjoittajasta. Nykyisin kirjoittajaksi useimmiten ilmoitetaan Francesco Colonna, sillä kirjan lukujen alkujen koristellut initiaalikirjaimet paljastavat akrostikonin tapaan seuraavat sanat: POLIAM FRATER FRANCISCVS COLVMNA PERAMAVIT, eli suomeksi "Veli Francesco Colonna rakasti Poliaa suuresti". Muitakin vaihtoehtoja teoksen mahdolliseksi oikeaksi kirjoittajaksi on esitetty – näistä nimekkäimpiä ovat Lorenzo de' Medici ja Leon Battista Alberti. Pitäydyn itse konventionaalisessa tavassa puhua kirjasta Francesco Colonnan kirjoittamana. Tekstin lisäksi kirja sisältää yhteensä 172 taidokkaasti toteuttua kuvaa, jotka kuvittavat kohtauksia tarinasta. Myöskään näiden kuvien tekijää ei tiedetä. Mahdollisiksi kuvittajiksi on esitetty muun muassa Benedetto Bordonea, Benedetto Montagnaa ja jopa Sandro Botticellia. Ripottelen tämän tekstin sekaan kuvia alkuperäisestä vuoden 1499 painoksesta, jotta kuvien luonne ja suhde tekstiin käy ilmi.

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili kertoo Poliphilo-nimisen miehen fantasisesta unesta, jossa hän kohtaa uskomattomia arkkitehtonisia taidonnäytteitä, kauniita nymfejä, suuria vaaroja sekä, lopulta, rakkaimpansa Polian. Poliphiloksen nimi tarkoittaakin joko "monen rakastajaa" (poli-philos) tai "Polian rakastajaa" (Poli-philos). Tämän kaksoismerkityksen huomioi myös yksi tarinan nymfeistä [s. 83–84; kaikki sivunumerot ja sitaatit ovat Joscelyn Godwinin englanninnoksesta]. Sana "Hypnerotomachia" on koostettu kreikankielisistä sanoista "hypnos" (ὕπνος, uni), "eros" (ἔρως, rakkaus) ja "mache" (μάχη, taistelu). Teoksen englanninnoksen alaotsikko kääntää "Hypnerotomachian" muotoon "The Strife of Love in a Dream". Suomeksi "Hypnerotomachia Poliphili" voisi kääntyä muotoon "Poliphiloksen Unilempitaisto".

Teoksen alkuperäisellä nimiösivulla lukee kokonaisuudessaan: "Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, ubi humana omnia non nisi somnium esse docet. Atque obiter plurima scitu sane quam digna commemorat", jonka englannintaja on kääntänyt muotoon: "The Hypnerotomachia of Poliphilo, in which it is shown that all human things are but a dream, and many other things worthy of knowledge and memory".

Teos alkaa hetkestä, kun Poliphilo vaipuu uneen ja löytää itsensä ihmeellisestä metsästä. Harhailtuaan jonkin aikaa hän kohtaa jättimäisen pyramidin jonka huipulla on korkea obeliski. Seuraavat noin neljäkymmentä sivua Poliphilo kuvailee kyseisen rakkennelman arkkitehtonista uskomattomuutta ja sen moninaisia koristuksia, kunnes hän kohtaa lohikäärmeen jota hänen täytyy paeta. Tämän jälkeen Poliphilo kohtaa viisi kaunista nymfiä, joiden kanssa hän ensin kylpee ja sitten matkaa tapaamaan heidän kuningatartaan. Tätä seuraa shakkiottelua esittävä balettinäytös. Tämän jälkeen Poliphilo kohtaa uuden nymfin, kaikkia aikaisempia kauniimman, jota epäilee omaksi Poliakseen, muttei ole tästä vielä varma. Lopulta he saapuvat suurenmoiseen temppeliin, jossa nymfi paljastaa todella olevansa Polia, Poliphiloksen rakas. Myöhemmin rakkauden jumala Cupido kuljettaa pariskunnan veneellään uuteen, entistäkin kauniimpaan paikkaan. Täällä paikalliset nymfit pyytävät Poliaa kertomaan oman elämäntarinansa. Polia kertoaa tarinansa, jossa Poliphilo kuolee, koska Polia ei osoittanut rakkautta häntä kohtaan, mutta myöhemmin virkoaa takaisin henkiin Polian sittemmin heränneen rakkauden ansiosta. Tämän jälkeen Polia kertoo saman tarinan Poliphiloksen perspektiivistä. Lopuksi Polia ja Poliphilo syleilevät, kunnes Polia haihtuu ilmaan ja Poliphilo herää unestaan.

Tässä teoksen "juoni" hyvin tiivistetyssä muodossa. Suurin osa teoksesta ei kuitenkaan koostu juonen tai tapahtumien eteenpäin kuljettamisesta, vaan eksessiivisestä fiktiivisestä ekfrasiksesta. Poliphilo kuvailee joka ikistä näkemänsä asiaa hullantuuneen rakastajan tarkkuudella. Joka ikinen pylväs, pensas, vaate, koru, rakennus, malja ja alttari kuvataan lähes uuvuttavan perusteellisesti. Etenkin unimaailmassa sijaitsevien rakennelmien arkkitehtuuria kuvaillaan teoksessa paljon. Jotta lukija saa käsityksen tästä ylenmääräisyydestä, tässä osa (vain osa) yhden Poliphilon kohtaaman rakennelman kuvailusta (sitaatin yli voi myös huoletta hypätä):

"This elegant and symmetrical open-air courtyard had canopies all around made from perfect gold: a wondrous and ineffable work.

The pilasters or semi-square columns were four paces apart, making seven equal divisions (the number most favoured by nature) and were of fine oriental lapis-lazuli, its colour delightfully enhanced by a scattering of tiny sparkles of gold. The fronts of the pilasters between the enclosing wave-moulding were exactly proportioned as to width and height, and marvellously carved with a charming assemblage of candelabra, foliage, cornucopias, little monsters, heads with leaves for hair, putti whose extremities turned into scyllas, birds, baluster vases, all of extraordinary inventiveness and design, sculpted from top to bottom in relief as if detached from its flat background. Thus the pilasters intervened in a harmonious and pleasing manner between the well-spaced golden panels. The capitals were made in concordance with the rest of the work. Above them stretched the straight beam carved with the requisite lineaments, with cylinders or little rods intercalated between the downward spirals. Then came the ornate zophorus, which contained an alternating pattern: first, bucrania, knotted with waving ribbons to two branches of myrtle hung with berries, and secured across the middle with loose swags of material; next, dolphins, with leaf-like gills and the end of their fins turning into leaves, their tails giving way to antique rinceaux, and putti holding on with their hands inside the curling tails. The dolphins' snouts were curved, with one part turning up toward the putto and the other curling inward toward an open-mouthed vase, and ending in a stork's head. The latter's beak was near the open mouth of a monster facing upward, and some beads were strung between the mouth and the beak. These heads had leaves for hair, and were placed in opposing pairs, making a leafy filling for the mouth of the vase. A linen cloth was tied to the handles of the vase and hung down, with its ends hanging freely beneath the knots. Everything was decorated in concordance with its placement and the material; and in the centre, above the spirallings, was a child's face flanked by outspread wings.

The zophorus continued, decorated by these and similar lineaments. Covering it was a suitable cornice, very finely finished and artfully made, and on the surface above this, perpendicular to the projections of the quadrangular order, vases of antique shape were placed at regular intervals. They were over three feet high and made from chalcedony, agate, vermilion amethyst, garnet and jasper, alternating in colour and subtly carved in various excellent designs. The bodies of the vases were principally decorated with straight, concave grooves, and their handles were masterfully made.

Directly above each of the wreaths there were little squared beams seven feet high, suitably attached to the cornice and made from bright gold with spaces in between them. Similar beams were joined horizontally above these upright ones, going all around and serving as an ideal support for the regularly-spaced topiary work. The vases that stood at the angles of the walls held both a beam and a vine, whilst out of the remaining vases there issued alternately a vine or a convolvulus, made from different types of gold. They spread their many branches in all directions, supported by the transverse beams, weaving around one another in elegant friendship and graceful concord so as to cleverly cover this entire courtyard. They formed an unbelievably rich ceiling with their variegated foliage, made from splendid Scythian emeralds that delight the eye (the one with Amymone carved on it was nothing to them) and with flowers of every season made from sapphire and beryl, distributed with great skill and artifice among the green leaves. There were also large gemstones shaped like various fruits, and bunches of grapes imitated by massed stones hanging down and coloured like the natural grape. All these excellent and refulgent things, matchless in value, incredible and almost unimaginable, were precious not only for their wonderfully noble material but also for the grandeur and finesse of their workmanship." [s. 96–98].

Suurin osa kirjasta kostuu tämänkaltaisesta kuvailusta. Erään suurenmoisen temppelin arkkitehtuurin ja koristeiden kuvaileminen kestää yhteensä neljäntoista sivun verran [s. 197–211]. Yhdennentoista sivun jälkeen Poliphilo sanoo: "Finally, to conclude this miraculous temple structure, it remains to say briefly…" [s. 208] ja jatkaa kuvailuaan vielä kolmen sivun verran. Jos Hypnerotomachia Poliphilia täytyisi kuvailla yhdellä sanalla, olisi se eksessiivinen.

Vaikka Poliphilo käyttää teoksen aikana satoja sivuja näkemiensä asioiden pikkutarkkaan kuvailuun, hän kiinnostavan oksymoronisesti myös toistelee useaan otteeseen, ettei pysty mitenkään kuvailemaan sitä, mitä hän näkee ja kokee: "Touching these divine matters, I am firmly convinced that it would be futile, however eloquent and facile one's tongue, to attempt a complete description of the lovely music, the sweet songs, the solemn and the comic dances, the festivities of the divine nymphs and noble maidens, their singular and incomparable beauty, and their rich, illustrious and elegant adornments." [s. 343], tai: "I think that the dignity and reputation of these things, with their miraculous and matchless workmanship, will be more appropriately served by my silence." [s. 361].

Yhtä ylenpalttisesti kuin Poliphilo kirjan alkupuolella kuvailee näkemiänsä arkkitehtonisia ihmeitä hän kirjan loppupuolella kuvailee riutuvaa rakkauttaan Poliaa kohtaan. En tilan vuoksi lainaa koko katkelmaa [s. 390–396], vaan vain noin ensimmäisen kuudenneksen siitä, ja lukija voi tahtoessaan sydämessään ekstrapoloida, miltä tämä kuuloistaisi kuusi kertaa pidempänä:

"Alas Polia – nymph of the lovely hair – my goddess – my heart – my life – and the sweet executioner of my soul – have pity on me! If, in your divine nature and your unique beauty, that virtue still lives by which my soul, having elected you as its sole ruler in this age and as its first lord, did not hesitate in its joyous offering but abased itself before you, pray be gracious, gentle and benevolent, to assuage my grave sufferings. I am well aware that I have not come hither at a propitious time, yet I have never lost all hope; and I feel myself dying because I can no longer bear this incessant misery. As a last resort, it seems to me better to die now, rather than to live burdened with the absence of your love. Thus I cheerfully expose myself to death, rather than living a miserable and painful life without your longed-for affection: better to perish instantly than to die daily! If perchance some god is afflicting me with inexorable severity, may he at least allow me to die by your hand, if I am not allowed a happy life. For if your angelic presence is removed from my sight, and this one and only solace and pleasure reft from me – a solace which I so much desire and of which I can never have enough – what worse evil or deadly peril could I suffer? I hoped for no other remedy to suit my bitter and unbearable langour than that the kindly heavens should allow me to see you again; otherwise I saw violent ruin threatening to overwhelm my tedious life. And just as the condemned man leaves off lamenting when he sees the inevitable blow about to descend, I surrendered my miserable life into the hands of the terrible sisters, no less unbalanced and at times maddened by tormenting love than was Attis, or Pentheus by his own sisters and by wretched Agave. I saw myself abandoned like Achaemenides left by Ulysses between Scylla and Charybdis. The oppressive heat seething in the confines of my heart afflicted me so much that I had no hope or desire but you alone, Polia, as my instant and healing medicine. I was unknown to you – deprived of you – abandoned by you. The more I dwelt during that absence on your striking features and celestial beauty, your lovely face and the elegant profusion of your rare virtues, the more bitter and pained I felt at not being able to enjoy them. On this account, miserable lover that I am, I endured so impetuously, so inadvisedly, and so precipitously those horrid affronts, those false blandishments and deceitful caresses of love, whilst hiding the pain and restless agitation which sometimes, nay often seized me in consequence. Yet I have willingly suffered these evil snares with such steadfastness purely for your sake, my sweet lady Polia. Alas, poor me!" [s. 390–391]

Eksessiivisyyden lisäksi tässä sitaatissa on nähtävillä toinenkin Hypnerotomachia Polipihilissa hyvin tiheään toistuva piirre, nimittäin viittaukset antiikkiin. Poliphiloksen unimaailma on eräänlainen fantastinen versio antiikista, ja Poliphiloksen antiikkiin kohdistuva rakkaus ja ihannointi käyvät selväksi jo varhain teoksessa: "This is why I was seized and overcome with pleasure and unthinkable happiness, and with such gratitude and admiration for holy and venerable antiquity, that I found myself looking around with unfocused, unstable and unsated gaze. [...] I gazed insatiably at one huge and beautiful work after another, saying to myself: 'If the fragments of holy antiquity, the ruins and debris and even the shavings, fill us with stupefied admiration and give us such delight in viewing them, what would they do if they were whole?'" [s. 57 & 59]. Kerran Polia toteaa suoraan: "Poliphilo, my best-beloved, I am well aware that you are extremely fond of looking at the works of antiquity." [s. 242]. Poliphilo myös useaan kertaan voivottelee oman elinaikansa (1400-luvun) kehnoutta verrattuna antiikiin: "I must use the vulgar speech, and not the Roman vernacular, because we are degenerate" [s. 47], tai: "[The bridge] was commendable for its eternal solidity, unknown to the myopic pseudo-architects of today who lack literature, measure and art" [s. 134].

Poliphilo pitää antiikkia ihmiskunnan sivistyksen ja taiteen huippuna, mutta nostaa unimaailmansa toistuvasti vielä antiikkiakin korkeammalle. Hypnerotomachia Poliphili on täynnä kohtia, joissa Poliphilo korostaa miten paljon upeampia hänen näkemänsä asiat ovat kuin mikään antiikista peräisin oleva. Asiat vertautuvat jatkuvasti sekä antiikin myytteihin että historiaan: "[The fruits] tempted the taste to an even higher degree than those which approached the famished mouth of Tantalus, and were more beautiful than those desired by Eurystheus" [s. 233], tai: "Such were the marvelous imitation of colours and the measured lines of perspective, the elegance of figures, fertile invention, artistic arrangement and unbelievable subtelty, that the famous painter Parrhasius of Ephesus could not boast of having been the first to create its like." [s. 251].

Itse kirja, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, on kirjoitettu oudolla ja ainutlaatuisella yhdistelmällä, jossa kielioppi on italian kielestä, mutta sanasto suurelta osin latinasta. Kääntäjä Joscelyn Godwin kirjoittaa esipuheessaan käännökseensä: "[Francesco Colonna] stretches his Italian constructions to the limit, with a breathless piling of clause upon clause that sometimes tumbles into incoherence. But they remain Italian, as do his lack of declensions, his use of articles and prepositions, and his verb-forms. His vocabulary, on the other hand, is not to be found in any Italian dictionary. Much of it consists of Latin words, the more recondite the better, which he adapts with Italian endings. A small but significant proportion of the words is Greek in origin." [s. ix].

Käännöstyötä koskien Godwin kirjoittaa: "But if one were really to convey the spirit and style of the original language, it would have been necessary to do as Colonna did: to invent new English words based on the same Latin and Greek ones, and to embed them in a syntax to match." [s. x] Tällaisen yrityksen sijasta Godwin valitsi käännöstyylin, joka pyrkii luontevaan englannin kielen käyttöön. Godwin kuitenkin antaa esimerkin siitä, miltä Colonnan kielelliselle tyylille "uskollinen" englanninnos voisi kuulostaaa: "In this horrid and cuspidinous littoral and most miserable site of the algent and fetorific lake stood saevious Tisiphone, efferal and cruel with her viperine capillament, her meschine and miserable soul, implacably furibund." [s. x–xi]. Ehkä joskus vielä saamme teoksesta Colonnan ainutlaatuista kieltä tunnollisesti mukailevan englanninnoksen tai – miksi ei – suomennoksen. (Hypnerotomachia Poliphili on käytännössä renessanssin aikainen Finnegans Wake.)

Eksessiivisyyden ja antiikin lisäksi kolmas toistuva elementti teoksessa – ilmiselvän rakkaus-teeman lisäksi – on erotiikka. Kun Poliphilo matkansa alussa tapaa viisi kaunista nymfiä, nämä tarjoavat hänelle virkistävää ja palauttavaa voidetta, jota sivellä iholle kylvyn jälkeen. Pian kuitenkin paljastuu, ettei voide ollutkaan virkistävää ja palauttavaa vaan seksuaalisia haluja herättävää: "I had reasonably assumed that the ointment I had used was for the comfort of my exhausted limbs, bu lo and behold! I suddenly began to be sexually aroused and lasciviously stimulated to the point of total confusion and torment, while these wily girls, knowing what had happened to me, laughed unrestrainedly. [...] I said [to one of the nymphs], 'Forgive me for twisting like a willow wand, but I am dying, if you'll excuse me, from the fire of lust.'" [s. 86–87].

Toistuva eroottinen aihe teoksessa on kielisuudelmat. Teoksen aikana tapahtuu useita suudelmia, ja suurimmassa osassa näistä on mukana kieli. Ja kun kieli on mukana, se todella on mukana. Tässä muutama esimerkki:

"I felt that this had the virtue of converting anyone, even one inept in love and extinct in desire. [...] they kissed each other more tightly and mordantly than the suckers of an octopus's tentacles; more than the shells that adhere to the Illyrian rocks or to the Plotae Isles. They kissed with juicy and tremulous tongues nourished with fragrant musk, playfully penetrating each other's wet and laughing lips and making painless marks on the white throats with their little teeth." [s. 183]

"As I contemplated her matchless being, a honeyed sweetness waxed deliciously within me. And sometimes, assailed by insatiable appetite and heavily oppressed by a burning and inopportune passion, I beseeched her inwardly with plangent words full of suave and vehement prayers, secretly longing for kisses; sweet, moist, and vibrant with the snake-like motions of the succulent tongue. I imagined myself tasting the extreme delight of that savorous little mouth, breathing its fragrant airs, its musky spirits and its untainted breath, and pretending to penetrate into the hidden treasury of Venus, there to steal, like Mercury, the precious jewels of Mother Nature." [s. 240]

"And as he hugged me tightly, my little round purple mouth mingled its moisture with his, savouring, sucking, and giving the sweetest little bites as our tongues entwined around each other." [s. 434]

"Then, winding her immaculate, milk-white arms in an embrace around my neck, she kissed me, gently nibbling me with her coral mouth. And I quickly responded to her swelling tongue, tasting a sugary moisture that brought me to death's door; and I was straightaway enveloped in extreme tenderness, and kissed her with a bite sweet as honey. She, more aroused, encircled me like a garland." [s. 464]

Ihmisten lisäksi Poliphilo lumoutuu romanttis-eroottisesti myös näkemistään rakennuksista: "I gazed intently at this [building] with my lips agape, my fluttering and mobile eyelids motionless, my soul enraptured, as it contemplated these scenes which were so beautiful [...] I was so amazed and absorbed that I was as though lost to myself." [s. 61], tai: "This sight [of the temple] gave me so much pleasure that I was moved immoderately by the ardent desire to see it properly close to, suspecting with good reason that it was a grand and ancient structure. [...] Alas, I dare not ask for this thing which drives me with such sharp and constant longing, though I am certain that once I obtained that which I desire so much and pursue with so fixed a mind, it would make me contented above any lover." [s. 197]

Hypnerotomachia Poliphili on outo, poikkeuksellinen ja ainutlaatuinen teos, ja siihen liittyvät mysteerit – kuka sen kirjoitti? kuka kuvitti? miksi teos on sellainen kuin se on? – ainoastaan lisäävät sen kiinnostavuutta. Pitkässäkään tekstissä ei ole mahdollista tarjota kattavaa kuvaa tästä eksessiivisyyden riemujuhlasta, mutta olen omassani pyrkinyt tuomaan ilmi sen merkittävimmät ja kiinnostavimmat puolet.

Hypnerotomachia Poliphilin alusta – ennen kuin itse tarina alkaa – löytyy runo otsikolla "Anonyymi elegia lukijalle", joka päättyy (Godwinin englanninnoksessa) säkeisiin:

"Behold a useful and profitable book. If you think otherwise,

Do not lay blame on the book, but on yourself."

***

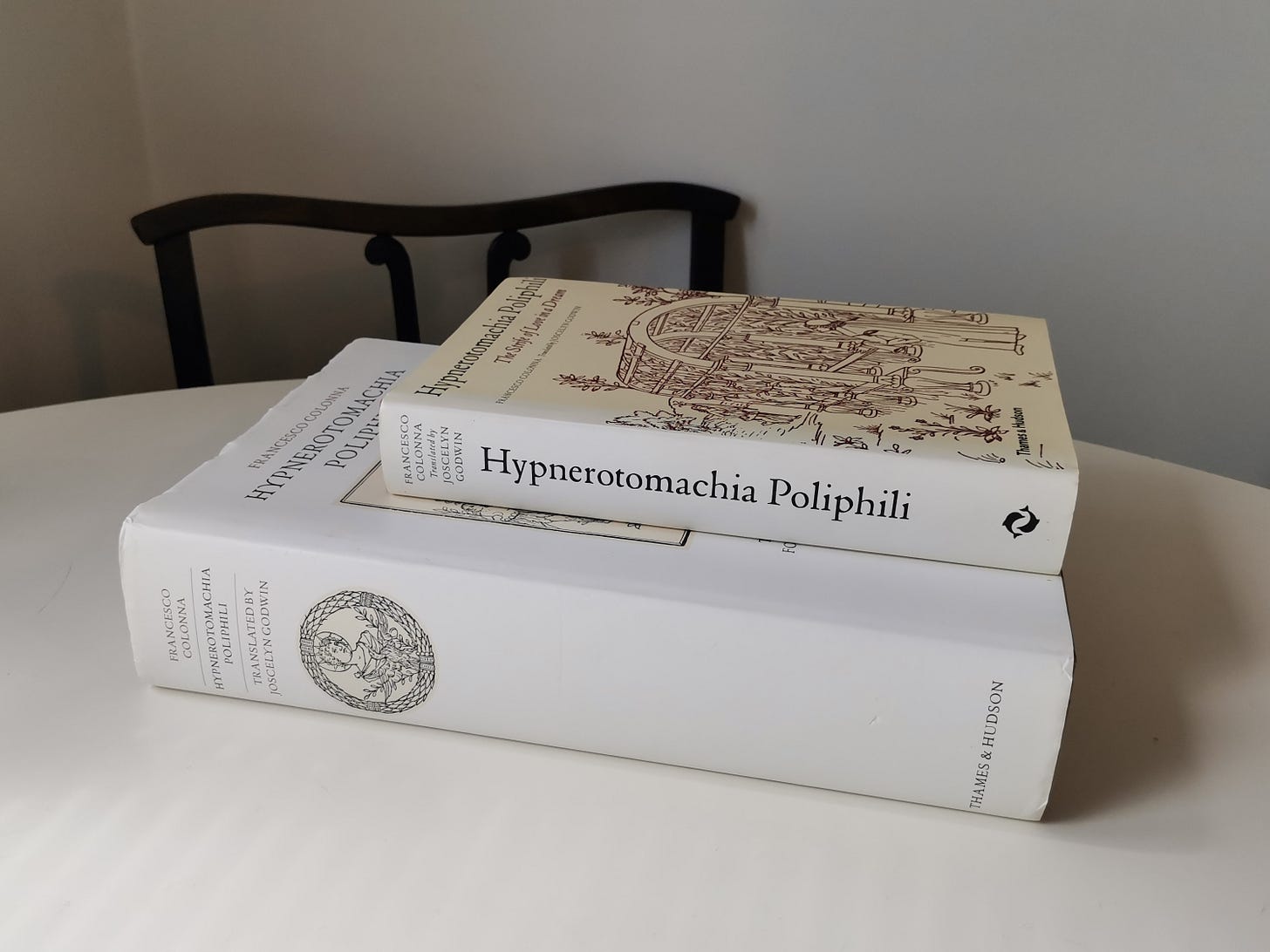

Hypnerotomachia Poliphilin ainoa kokonainen englanninnos on Joscelyn Godwinin, ja tästä on olemassa kaksi erikokoista painosta. Alkuperäinen painos, joka julkaistiin vuonna 1999 – kun Hypnerotomachia Poliphili täytti 500 vuotta – vastaa sivukooltaan alkuperäistä, Aldus Manutiuksen painamaa editiota, ja on siis varsin iso, tarkalleen 31 x 20 cm. Myös teoksen typografia, kuvat ja kuvien asettelu suhteessa tekstiin on säilytetty alkuperäisteosta vastaavina. Myöhemmin englanninnoksesta otettiin pienempi, ns. normaalin kirjan kokoinen painos, jonka sisältö on identtinen suuremman kanssa, ainoastaan pienemmäksi skaalattuna.

Kattavia kommentaareilla varustettuja painoksia Hypnerotomachia Poliphilista ovat Giovanni Pozzin ja Lucia A. Ciaponin toimittama editio (Editrice Antenore, 1968), joka sisältää alkukielisen version tekstistä, ja Marco Arianin ja Mino Gabrielen toimittama editio (Adelphi Edizioni, 1998), joka sisältää sekä alkuperäistekstin että italiannoksen.

***

Vuonna 2004 julkaistiin Ian Caldwellin ja Dustin Thomasson The Rule of Four -niminen jännitysromaani (suom. Markku Päkkilä nimellä Neljäs siirto, 2005), jossa Hypnerotomachia Poliphililla on merkittävä rooli. Kirjan päähenkilön, Thomas Sullivanin, edesmennyt isä oli Hypnerotomachia Poliphilista kiinnostunut renessanssin tutkija. Romaanin tapahtuma-aikana myös Thomas päätyy teoksen äärelle, sillä hänen ystävänsä Paul Harris on kirjoittamassa siitä opinnäytetyötään. Tutkimuksen edetessä Hypnerotomachia Poliphilista alkaa löytymään yllättäviä matemaattisia salakoodeja ja muita mysteerejä – joita teoksessa, nota bene, ei todellisuudessa ole. Teoksen salaisuuksien selvittäminen johtaa jännitysromaanin henkilöt moniin ongelmiin ja vaaratilanteisiin. Hyvää kirjallisuutta en voi väittää romaanin olevan, mutta jos Hypnerotomachia Poliphili kiinnostaa, on The Rule of Four omalla pinnallisella tavallaan ihan viihdyttävää luettavaa. Roomanissa on paljon historiallisesti ja sisällöllisesti paikkansapitävää tietoa Hypnerotomachia Poliphilista, mutta varsin nopeasti tämä alkaa sekoittumaan teosta koskeviin fiktiivisiin faktoihin. Hypnerotomachia Poliphilin englannintaja Joscelyn Godwin julkaisi vuonna 2005 kirjan nimeltä The Real Rule of Four, joka toimii historiallisena ja sisällöllisenä oppaana sekä Hypnerotomachia Poliphiliin että The Rule of Four -romaaniin ja näiden väliseen suhteeseen.

***

Muuta suositeltavaa luettavaa, jos Hypnerotomachia Poliphili ja sitä koskevat aiheet kiinnostavat:

Helen Barolini - Aldus and His Dream Book (1992, Italica Press)

Liane Lefaivre - Leon Battista Alberti's Hypnerotomachia Poliphili: Re-Cognizing the Architectural Body in the Early Italian Renaissance (1997, MIT Press)

Oren Margolis - Aldus Manutius: The Invention of the Publisher (2023, Reaktion Books)